Play it safe!

How to make prophecies of doom come true - and profit from it!

AI safteyism vs. E/Acc is the latest instantiation of the war of memes that has been ravaging societies and hampered progress for millenia.

AI safteyism belongs to the class of “cynical philosophy”. Cynicism is the denial that progress has happened, is happening, or would be a good if it did happen. As so often, AI safetyism is paired with the idea that a problem is insoluable (“Humanity is too dumb to control an omniscient AI!”) and therefore requires the entrenchmentof new taboos, which justify — or necessitate, rather — violence against transgressors.

E/Acc is an optimistic philosophy, recognizing that evils (=anything that causes suffering or impairs human thriving) are inadequacies or errors in existing knowledge. E/Acc follows David Deutsch in believing that there are no limitations, other than the laws of nature, on our ability to eliminate evils by creating knowledge. Knowledge is created by iteratively guessing improvements creatively and criticizing them, and prior knowledge.

You will be hard pressed to find any innovation anywhere in written history, that was not repressed for its unknown, but oh so certainly catastrophic consequences on race, royalty, religion and — most importantly — remuneration.

The larger and more transformative a technology, the bitterer the fight.

While today’s battle is waged about artificial intelligence, promising the scaling of many important tasks, from driving, construction, farming, accouting, to creating art, music, and science, well beyond our human numbers, can we learn something about the cycnical playbook by looking at recent battles in this war of memes?

Nuclear Power

There is probably no other technology offering as much energy security and indepedence as nuclear power. It promises clean energy at the scale needed to provide all 8 billion of us with a high standard of living. A typical reactor stores months to years worth of fuel in its core; fast reactors can convert denatured uranium, which has been produced as by-product of the enrichment process, into usable fuel. If and when fast reactors work as envisioned, the US would have amassed enough uranium already for all of its power consumption for a few thousand years at current levels.

A power plant, once constructed, can run for 60-100 years. It’s hard to apply political pressure by threatening to cut off energy supplies, if the intended target can utilize such vast stores of energy.

Just like with oil, where “crude” doesn’t exactly help you to power your car, for nuclear you need regulatory complex, highly controlled, specialized enrichment hardware to turn “crude” uranium into something useful.1

When a country has mastered building and operating enrichment equipment and the chemical conversion processes that are necessary, there is not really anything stopping that country from using these enrichment facilities to produce weapons-grade uranium. Except the lack of will to do so, of course.

A country that has access to as much energy as it wants, and has also access to a sizable arsenal of devastating weapons2 is dangerously independent, hellishly hard to control.

Once the USA had mastered uranium enrichment and the controlled chain reaction for power generation, it open-sourced a reactor design that was derived from a military submarine in a wholly unprecedented display of altruism as soon as it was working; funneling almost all energy/minds to that design, which coicidentally(?) requires a constant supply of fuel, that countries adopting it could only get from one place at the time,3 and which does not produce new fuel.4

After most of research and industry was locked in on one type of reactor, and even that in many respects suboptimal reactor type became too competitive for entrenched interests, miraculously, the capacity to build these reactors seems to have vanished. While it was possible to build reactor for <1000$/kW5 in the late 60s, reactors that are still running, mind you, it’s apparently not possible in 2023, despite having computers, robots and nascent AI.

Maybe we just started to be bad at building complex power plants?

Do we see the invisible hand of the market here, which doesn’t favor such projects? Or is someone else’s hand very involved?

Isn’t it strange, that we get countries from all over the world to work together to spend $40G on a fusion plant that will never produce electricity, but we cannot spend a tenth of that money to derisk several fast fission reactor types, which would convert a liability (nuclear waste) into a hugh asset?

Why do we fail to spend a few millions in corrosion testing to get new coolants ready to go? How is it even possible to drive the licensing process to cost several hundred millions of dollars, lasting more than a decade — for reactors we have been building for almost 70 years?!

Given such an environment, an industry won’t attract energetic, bright, young minds. In fact, it looks exactly like it’s designed to be as appaling to that demographic as humanly possible. Everything is deliberately slow, hard and unimagnibly formalistic, lawyerly and expensive. Is it any wonder that such an industry is relegated to a pathetic, zombie-like existence?

Nuclear has become so unattractive as a competitive industry, that only state-backed companies from China, Russia, Canada or South Korea are building power plants around the world, while private companies appear less than competitive at the moment.6

Okay, we did not get the abudant energy that nuclear promises, but at least we have been kept perfectly safe, right? Of course not!

I am not talking about TMI, Chernobyl, Windscale, Majak, Hanford, or Fukushima. While these incidents fueled the public’s imagination, their death toll would hardly make any list of bad industrial accidents. I am talking about nuclear arsenals7 in the hands of Stalin, Mao, Kim Jong-Un, or Putin.

We managed to get access to the most devestating form of nuclear power (thermonuclear weapons) to exactly those psychopaths, that the regulations, agencies and committees were ostensibly intended to keep us safe from.

We sacrificed the prosperity of unlimited nuclear energy for nuclear safety, we got what we were most afraid of: big red launch bottons on desks of men you would rather have sit behind bars.

But that is certainly just a one-off, right?

Biotech

Biotech promises the creation of organisms specifically designed for human needs. Governments regulate work on gene editing heavily. It took 30 years to get a fast growing salmon and a rice that keeps children from getting blind to market; it has become so expensive, that we have to rely on major agro-businesses like Monsanto to bring patent-protected innovations to market.

The nightmare scenario has always been that someone might taint nature by engineering and releasing “something” that is deadly for humans or other parts of the ecosphere.

Yet, a government funded lab (is strongly suspected to have) released a virus, engineered to target human cells. The idea seems to have been to collect and then manipulate rare viruses for the development of vaccines in preparation for the case of a virus making the jump from animal to human naturally.

The virus killed 8+ million people, led democracies to restrict the freedoms of millions of people, led to domestic terrorism charges against protester, and spawned a whole censorship-industrial complex geared at supressing skeptics of the official narrative. Why? Are we too afraid to ponder the possibility that underpaid research scientists with some brains are capable of creating viruses that can kill (have killed?!) millions? Right under the nose with of the two most powerful governments of the world and with public funding?!

We sacrificed the promises of gene edited organisms to bio safety, we got the (probably) carelessly released weaponized viruses, masks, closed schools, and lockdowns.

How about drugs and medicine?

Pharmaceutics

It costs billions to get a new drug to market concentrating the market considerably. Many people are still prohibited from accessing experimental medicine as their last chance of staying alive, because it is too risky. We swallowed the “risk-free” OxyContin cleared by the regulatory agencies instead.

Sure, that started the opioid crisis and led to fentanyl, made in Mexico from Chinese precursors, killing tens of thousands of Americans annually.

But at least we still jail those pot heads for using cannabis as pain medicine!

We don’t even think about things like terrorists using drones for spreading widely available fentanyl over crowded stadiums, despite paying so many agencies to protect us from dangerous substances.

We sacrificed the promises of new medicines for treating ever more diseases (maybe even aging!) to drug safety, we got cartels, corruption and corpses instead.

We could also talk about being protected from raw milk, while being fed the sugarized food pyramid, or being protected from recessions, while creating the great depression and “too big to fail” banks, but that’s for another day.

The Safetyism Playbook

If we were to generalize the experience with cyncial X-safetyism so far, we would find roughly the following phases, after a technology shows some promise to be truely disruptive and progressive. I do not claim that these are always deliberate or orchestrated. Maybe these “baptist and bootlegger”-alliances happen organically, despite creating clear winners and losers?

Wait for the release version 1.0 with significant upwards potential.

Make it anathema socially, by anointing a group of insufferable, probably clinically depressed people and paying them to let their fatasy of doom run wild about all the ways something could go wrong, however far fetched. Amplify these nightmares by repetition in controlled media.

Publically shame or cancel anybody trying to give proper context by presenting costs AND benefits of the technology, its track record as opposed to prophecies of doom, as well as benefits AND costs of regulation as “stupid, uncaring, evil, genocidal x-denier”.

Supress their message as much as possible.Once public (or at least published) opinion is sufficiently hostile, use the dark fantasies of that group as basis for writing “safety” regulations to protect the public from the technology.

To really rub it in, bestow a council or committee entirely drawn from that doomers with official and arbitrarily veto powers over any innovation.

Suck the energy out of the sector: use the regulation to make it hard: slow, capricious, costly, protracted. From time to time, allow some hope, crush it arbitrarily,

Form/Select quasi-monopolistic state champions with great connections and career paths from industry into government and vice versa.

Once the tech is hard enough to scare away entrepreneurs and investors, build deeper moats. Government contacts give access to research grants, laboratories, bespoke testing faclilities, access to regulatory hearings, participation in creating binding standards, protection from lawsuits, etc.

Only the previously selected champions have the capacity to participate.Instantiate the most horrible version of the new technology as weapon.

Lionize the regulators for supposedly protecting the public, no matter how inept or wasteful they appear to be.

What do you think new regulations on AI will bring us? Will AI be sufficiently different to beat the playbook?

Or will it end up behind tall paywalls and in military (or militants’?) weapons?

What are your ideas to stop that from happening?

Canada’s very own reactor design, the CANDU, does not require enrichment of uranium, but enrichment of hydrogen to work properly. After the export of some of the technology to India, it was blamed for India’s successful nuclear weapons test. The story is that a CANDU reactor produces plutonium with a relatively high fissile content (compared to light-water moderated reactors), if run normally.

For all practial purposes, that does not seem to be a problem at all, because the fissile content is still so bad, that you can only theoretically make a “fizzle weapon” out of it. If you want a sophisticated weapon, you need a dedicated weapons reactor for that. But despite this, the CANDU reactor has been frowned upon after India’s test. Its construction has been made illegal in many jurisdictions, due to a technicality; a positive void coefficient. Yet, the CANDU remains the only one of the four often constructed reactor types, which did not suffer a melt accident (PWR → TMI, BWR → Fukushima, LGWR → Chernobyl)

A lot of work from Canadians, not least Chris Keefer’s Canadians for Nuclear, was necessary to restart interest in this design, which has a stellar record around the world from a construction and operation perspective.

Refurbishments and new builds are now on the table. It remains to be seen, if that will be successful.

Meanwhile, India has developed an offshoot of the CANDU technlogy, the IPHWR-700, and is deploying it in “fleet mode”.

The US, India, Pakistan and Israel operated heavy-water moderated, non-CANDU production plutonium production reactors for their weapons programs for quite some time.

Having a large stash of rather uncontroversial LEU, can be a real military asset, if you have enrichment technology. LEU has <5% U235 content and is as valuable to bomb builder as “a bag of apples”. The minimal amount for LEU to build a bomb-like critical mass is “infinite”, it’s just not physically possible.

But large LWR will get loaded with 90t or so of LEU; approximately a third of the fuel is replaced during refueling.

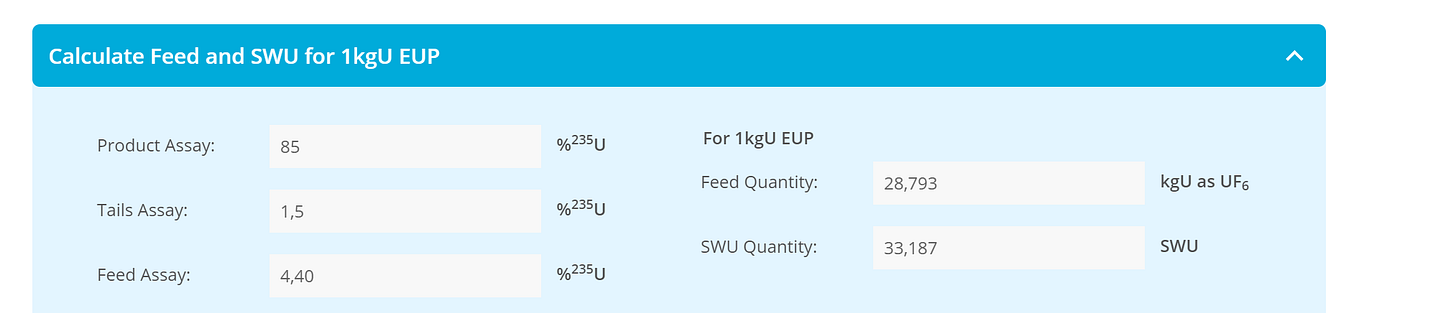

Enriching the 30t of LEU from natural uranium every year will take more than 100 000 kgSWU. If you have the capacity to do that as a country and you have a full core of LEU lying around as spare, you can easily convert lots of it into weapons material quickly. You need approximately 25kg of LEU at 4.4% enrichment and 35 kgSWU to get 1kg of 85% enriched HEU, usable as weapon.

A third of your enrichment capability will thus produce 1t of HEU from that completely legal LWR core; enough for something like 50 nuclear weapons in 4 months.

A country that has mastered enrichment for commercial operations, can acquire nuclear weapons. This might explain the various Iran deals and the Stuxnet attack on Iran’s enrichment capabilities.

Times have changed. Unfortunately, Russia is currently providing ~50% of world enrichment services and apparently doesn’t shy away from using them to apply pressure.

There are two viable pathways to breeding new fuel: uranium-plutonium und thorium-uranium. The latter can work with fast and thermal reactors (as proven by Shippingport’s third core), the former only works with fast reactors.

A fast breeder reactor could be used to produce sizable amounts of weapons-grade plutonium-239, the uranium-233 bred from throrium is purely fissile.

Chris Keefer repreatedly stressed that large, government-supported or -owned companies are running circles around the supposedly more nimble and agile market forces.

While I am not as far left on the anarcho-capitalism ← → centrally planned society spectrum, as I used to be, I still find it irritating that he is right. As a rule of thumb, if something like this happens, the heavy hand the government is tipping the scales somewhere. Regulations are a likely culprit.

As an anecdote, from all the designs currently pondered, the NRC was quick to grant a license to a reactor that relies on unavailable fuel (HALEU), in an unavailable fuel form (TRISO), cooled by an unavailable coolant (FLiBe), made from unavailable Li-7.

Oklo’s submission for a sodium-cooled fast reactor was rejected.

Following that logic, the only types of GenIV reactor having any chance of a timely license, are those that use LEU, like Terrestrial Energy’s IMSR or a fuel form (TRISO) that increases the costs of recycling.

The war in Ukraine has rekindled interest in Westinghouse AP1000s and GEH BWRX-300s designs in Eastern Europe (Poland, Ukraine, Bulgaria). If these bids are supported by government subsidies or “non-market” considerations is unknown to me.

Nuclear weapons are frightening.

There is nothing that you as individual can do to protect effectively against them. Burying yourself alive in a prison of your own choosing doesn’t count as attractive “solution” for me; but I get why people sepend a lot of money on something like that for ease of mind.

I do believe that nuclear weapons, especially the fractured security landscape of Europe (UK and France as independent actors, Germany, Netherlands, Belgium, Turkiye, Italy having access to them via NATO), did make the situation complicated enough to prevent Soviet planners from convincing politicians of any “advantage” that a first strike might have had. Is the terror of total annihilation a solid basis upon which peace can be build? Pretty much looks like it!

Maybe Greenpeace is wrong on both parts of their name.

Preventing nuclear technologies to proliferate is not only not green, it might be the reason for why we still have so much conflict in various regions.

Spreading the technology to countries like Sweden, Poland, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Saudi Arabia, would alter the face of geopolitics considerably;

Chinese or Russian expansionism might become too costly, the struggle over preeminence at the Gulf of Aden could come to a halt.

Mearsheimer made the case in 1993 that keeping nuclear arms (remnants of the Soviet era) in Ukraine would have increased its chances of surviving as coherent nation. The events of 2022 give some support for that point of view.