We can’t ignore the facts!

... unless we really need to

This will be the second of a few posts about the Rawlsian conception of justice, which I find useful.

So first things first:

The basic framework is “contract theory”: That means we’d like to envision a just system as something people would voluntarily opt for; they’d contractually specify what they will do or refrain from doing, how they will deal with non-compliant parties to the contract, what their duties, obligations and privileges are.

In other words: the system is so good, everybody wants to be in it.

Nothing hard about designing that, right?

If you were conscious at any moment during the 21st century and witnessed any political debate, you know it’s anything but.

I believe a lot of the political divides can be traced back to a different assumption about the importance of “equality of outcome” vs. “equality of opportunity”.

Formally, the latter is called “pure procedural justice”. It obtains “when there is no independent criterion for the right result: instead there is a correct or fair procedure such that the outcome is likewise correct or fair, whatever it is, provided that the procedure has been properly followed.” [Rawls, S.86]

This can be exemplified with gambling. If people participate in a game of poker, they will leave the table with whatever is the outcome of their bets. There is nothing inherently fair about one distribution over another. If everybody followed the mutually agreed upon rules, that is.

There might be no way to credibly get to a “just” goal. At least I can’t see one. My reason is simple: we can’t agree on what that would look like, because even the identical picture might no be seen the same. What would a fair distribution of winnings in a game of poker look like? Let’s say we are dealing with two players and can somehow agree that 2-to-1 split in favor of the winner is ideal.

Does it matter, if the winner got there with ace quints? I think so. How anybody got to where they are seems important, eminently important. Did they do it within the rules all of them promised to adhere to? Did anybody take advantage of other people? Did anybody overuse a common resource? Did anybody clandestinely shift down-side risks to other people, while keeping the up-side chances? A different interpretation on questions like these looks like a sure-fire way for violence and unrest. I’d prefer to avoid that.

So if we can’t create an end state, a goal, that we consider just, maybe we can create a system that people would want. Something that balances chances and manages risks well enough to get people to subscribe to it. Maybe they’d even pay for it? Are systems of government export restricted?

This seems like the more productive route to go. Let’s look where it ends up.

If we are trying to find systems that work, how would Rawls’ hypothetical parties of the contract design such a system?

When we deal with real people, they’d probably blabber non-stop about how their particular characteristics and situations are the most important and should be enshrined as the ideal. It is of course legitimate to stand up for ones’s interests.

But personal bias will make otherwise reasonable people go to war to get what they want.

So the project is dead in the water from the getgo? Not so fast!

“The Veil of Ignorance” is Rawls’ attempt to answer that problem and get rid of pesky and biased debates about personal gain.

The idea is to restrict information to the general and discard personal information, when contemplating what systems would be beneficial for society at large.

First of all, no one knows his place in society, his class position or social status; nor does he know his fortune in the distribution of natural assets and abilities, his intelligence and strength, and the like. Nor, again, does anyone know his conception of the good, the particulars of his rational plan of life, or even the special features of his psychology such as his aversion to risk or liability to optimism or pessimism. [Rawls, S.137]

What would that change? Well, if you are designing a system that controls the distribution of rights, biases are best avoided, if you don’t know where in the system you will end up yourself. It’s akin to distributing a cake: it’s a great idea to let the person who slices it have the last pick. It’s a design that incentivizes equal shares.

Few people would see abominable poverty as “necessary” or “beneficial”, if they could be affected by it themselves. Likewise, there will be few people demanding special restrictions on the grounds of class, race, gender, sexual preference, etc., if they can’t be sure they won’t be on the wrong end of the power disparity.

The veil of ignorance also eliminate “unholy” alliances, where certain groups bargain and collude to gain advantages for themselves by shifting costs or risks to other groups. A particularly common and regrettable practice of current instantiations of the democratic process.

By removing specifics, the reasoners behind the veil of ignorance are forced to reason about “representative” persons, the mean and the variance of the resulting distributions are what needs to get managed. The resulting distributions are probably going to be too complex to handle analytically, but fortunately computer sciences can help us out here with a method utilizing randomness, namely Monte Carlo techniques, to deal with that.

You sample a bunch of hypothetical people, run them through the system and see where they end up. You do that a lot and you will get a pretty good proxy of the “true” distribution.

The core of what these hypothetical reasoners behind “the veil of ignorance” would come up with, is captured in these two principles:

First: each person is to have an equal right to the most extensive basic liberty compatible with a similar liberty for others.

Second: social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so that they are both (a) reasonably expected to be to everyone’s advantage, and (b) attached to positions and offices open to all. [Rawls, S.60-61]

To get back to the cake analogy: you would want everybody to have the same size of slices, except when there are good reasons not to do so. For example, the baker could get a greater slice to keep him motivated to make such fantastic cake; if it is open to anybody to become a baker.

Order is important with these principles. The first principles can’t be nullified by the second. This constraint helps to avoid a problem arising in classical Utilitarianism: how to make interpersonal comparisons? Depending on the choices for “utility”, how to aggregate them , how to optimize that function, (max(f) , max(min(f))?) and what constraints you impose on the problem, it might be “optimal” to satisfy a small group of sadists, if their pleasure is just intense enough. This is obviously a solution no Utilitarian is satisfied with.

The preeminence of the first principle states that you can’t enslave or eradicate certain subgroups on basis of their identity, because other people would “reasonably expect” to gain by that.

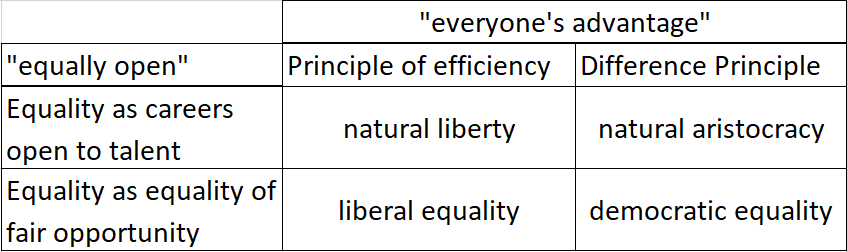

The second principle has two parts, each of which has two independent interpretations, resulting in four possible arrangements for society:

These will be the topic of a future post.

Assuming deliberate ignorance has brought us to a theoretical arrangement, which looks quite similar to liberal democracy. “Equal rights” are one of its cornerstones, especially with respect to the right to vote, which we don’t restrict (anymore) on the basis of race or gender, intelligence, class or employment status. We also arrived at a negation of nepotism and heritable leadership and at something, which reminds of a redistributive welfare state, but seems way more stringent. We’ll explore that in the future as well.

I’d like to end by noting how amazing it is that willfully ignoring certain facts leads to a set of principles that resemble today’s dominant form of government so much.

In a certain respect, this makes the popular quip that politicians are “know-nothings” a lot less insulting that it seems intended to be.