Inertial Laser Fusion

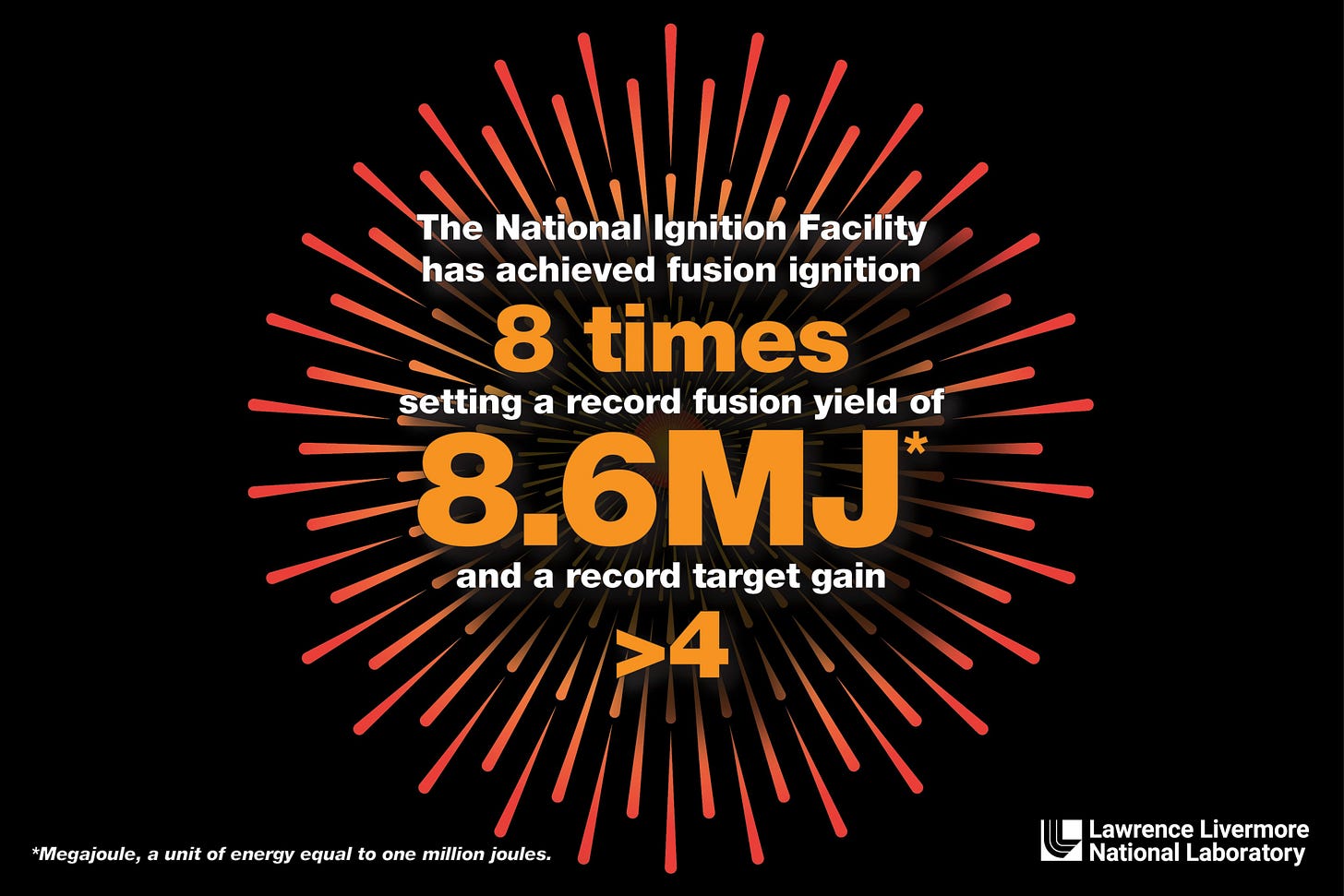

Humanity’s first burning fusion plasma outside of a nuclear weapon was achieved 3 years ago on December 5th, 2022 at the NIF. Since then, remarkable progress on the yield of the fusion reaction has been made.

This first spark of civilian nuclear fusion also lit the competition for the first commercial nuclear plant.

Let' us look at the different approaches to inertial laser fusion.

w

The National Ignition Facility

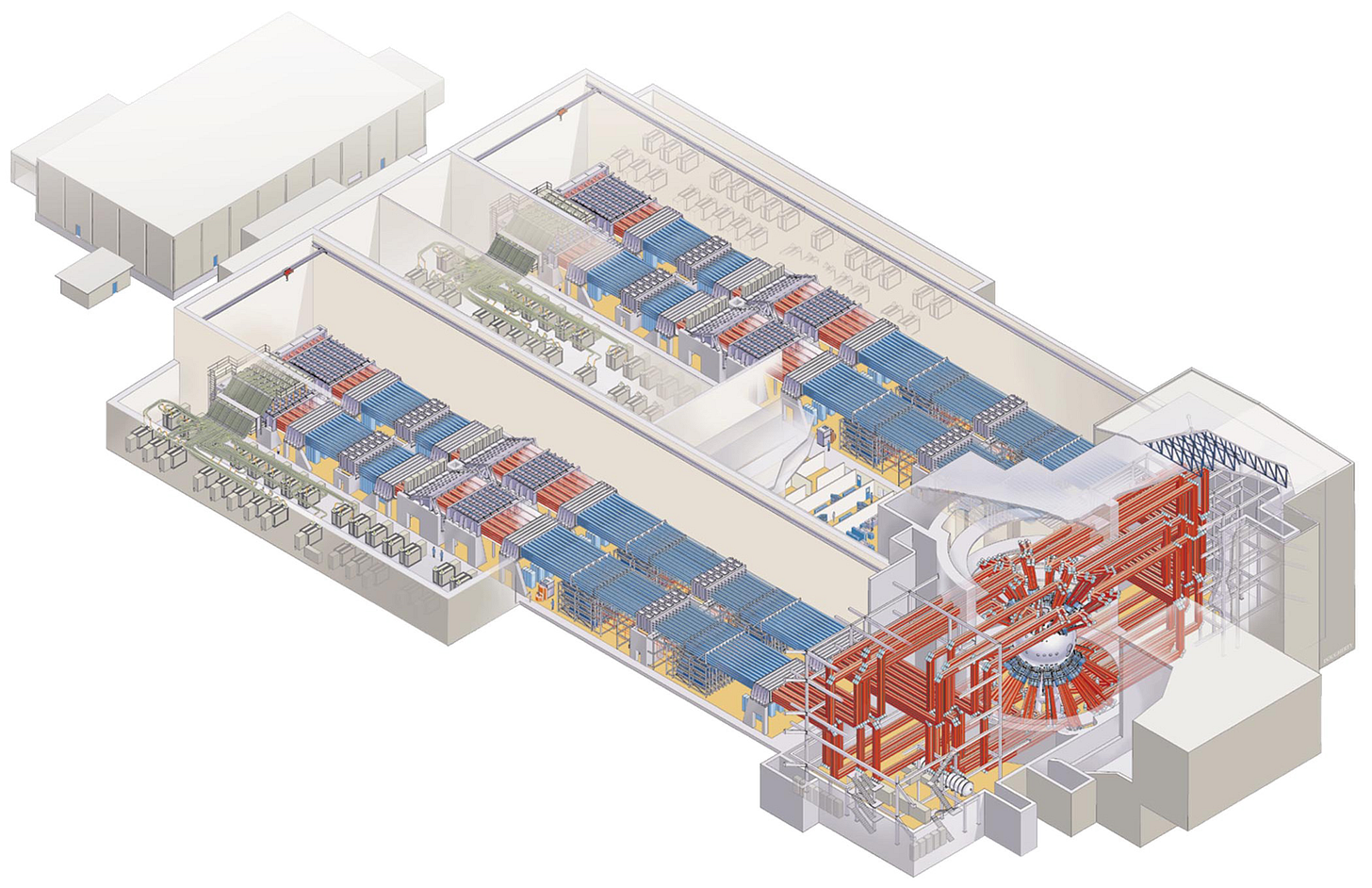

The NIF was originally designed to help with the stewardship of the US nuclear arsenal. Construction began in 1997 and was completed 5 years behind schedule and at almost 4x its original budget.

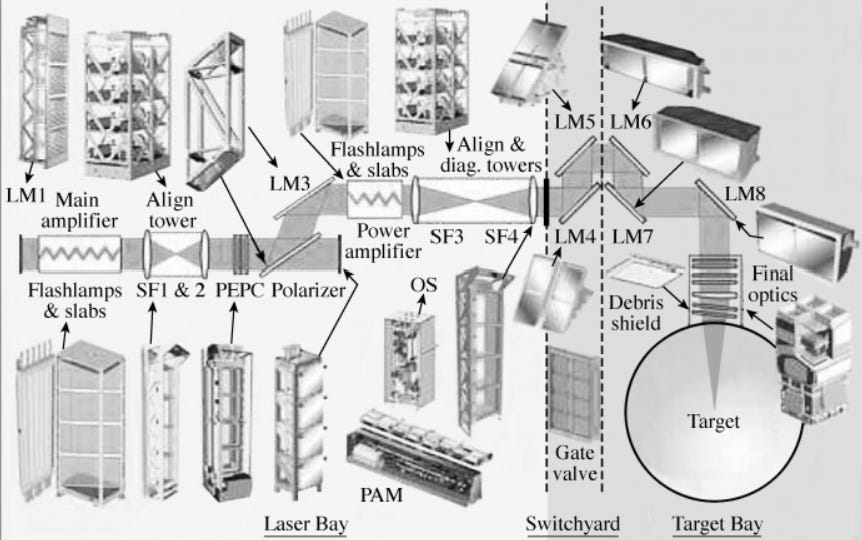

It hosts 192 laser beam lines, each of which uses a rather complex array of components to generate, amplify and focus the laser on the target.

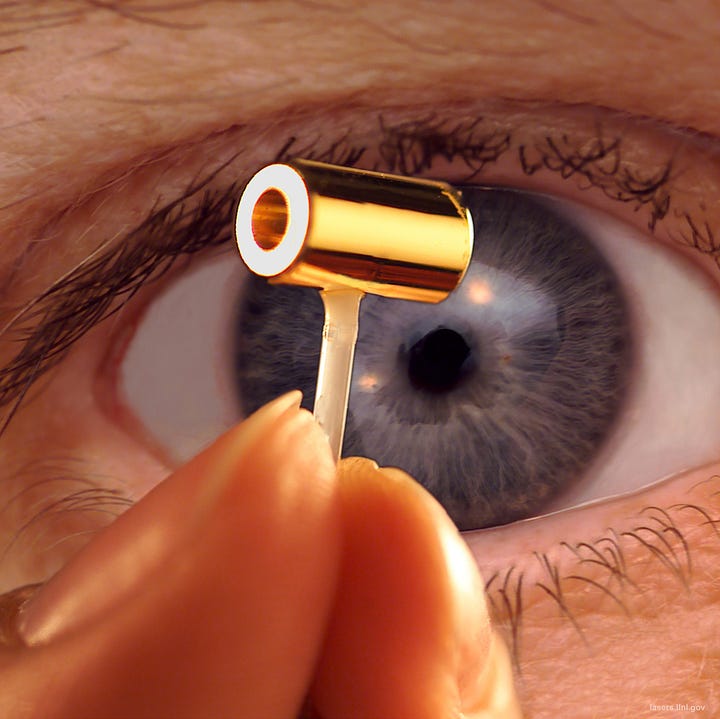

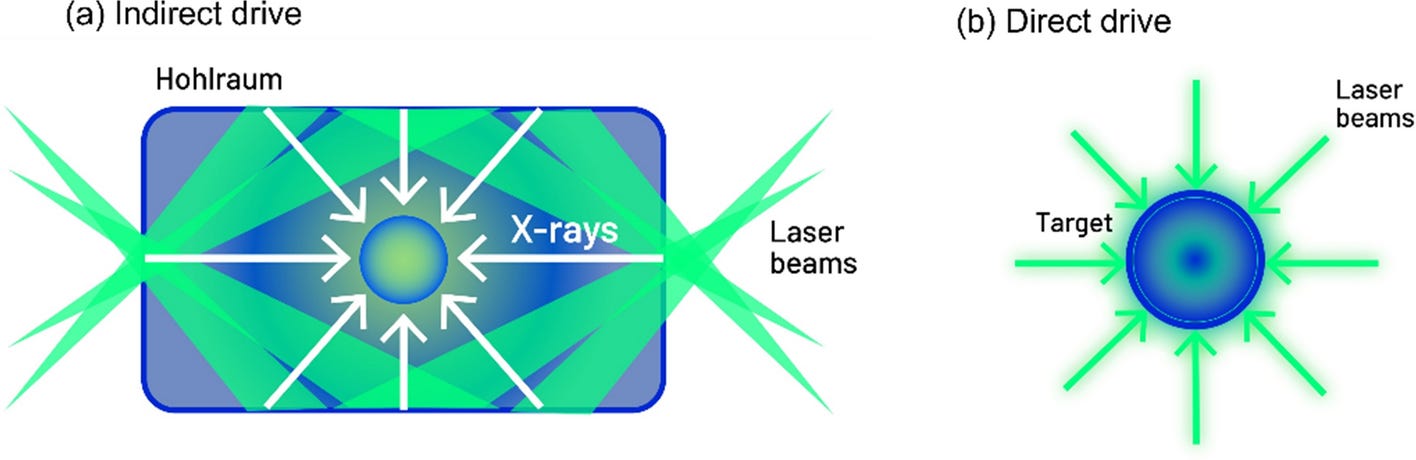

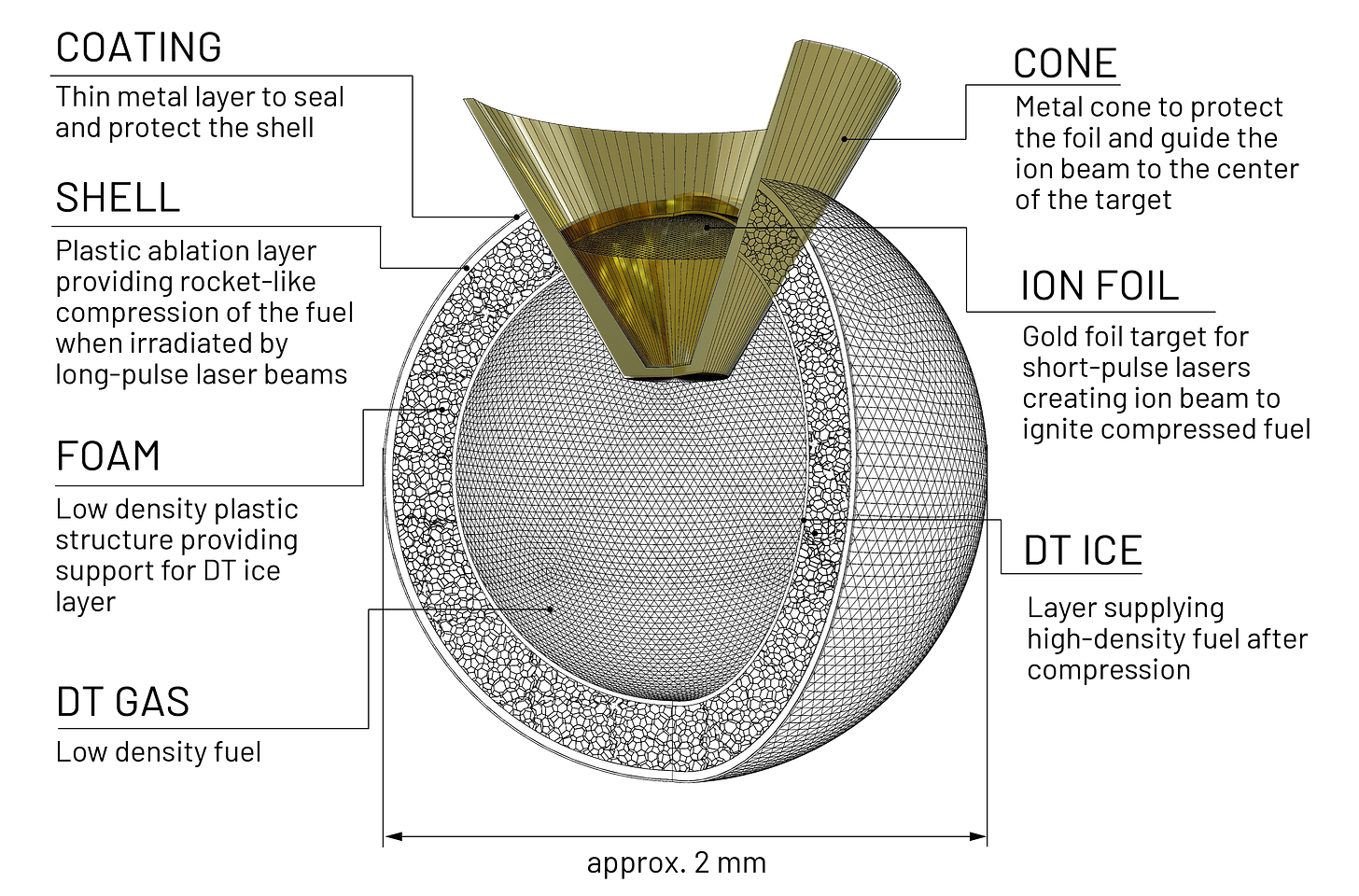

The “target” is a small ball of hydrogen ice (a 50/50 mixture of deuterium and tritium) inside of a capsule made of gold. This capsule, callled a hohlraum, is essential to NIF’s “indirect-drive” approach.

Instead of targeting the laser directly on the fuel and trying to “squeeze” it hard enough, which is called “direct-drive”, NIF’s lasers are actually aiming into the hohlraum, instead of onto the hydrogen ice ball. The impact of the laser onto the hohlraum’s inner wall converts the lasers’ energy into X-rays. These X-rays are compressing the fuel symmetrically from about water’s density to approximately 100x the density of solid lead. The indirect drive helps to prevent asymmetric compression. But this comes at a cost: at NIF, only roughly 15% of the energy of the laser pulse makes it to the actual fuel in the form of X-rays.

The lasers’ power output is considered to be close to the minimum physically necessary for achieving ignition. They were designed in the 90s and are rather inefficient by today’s standards, their delicate optics need hours to cool down after each shot. They waste a lot of energy by relying on the indirect-drive method.

In short, the NIF can neither deny its age nor its origin as a research facility for nuclear weapon stewardship, rather than as a commercial power plant. (Also not having any method of converting fusion power into electricity might have given the last point away)

And this is where the different fusion startups try to improve on NIF.

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery

Two companies come to mind, which try to stay as close to the proven physics of NIF as possible. One is Longview Fusion founded by Edward Moses former Project Manager and Director of the National Ignition Facility. The other is Inertia, which has recently been founded by former NIF Lead Target Designer Annie Kritcher and Mike Dunne, who led the US program to design a fusion power plant based on NIF.

These companies are closest to the original NIF, but they try to improve on various components. Inertia, for example, is looking at using 10 MJ diode-pumped, solid-state lasers, which are roughly 10x as efficient in converting electricity to the right kind of light. That is roughly 4 to 5x more energy than NIF can offer, fired at 10 Hz on scaled up NIF targets. 10 MJ has been compared to roughly the energy of a truck at highway speed, fully loaded, ramming into a target the size of ball bearing and coming to a full stop within a billionth of a second.

The much more powerful lasers should be able to cope with imperfections in the mass-produced targets, which are supposed to cost less than $1 a piece, but producing a gain of 45 (instead of NIF’s current world record of 4).

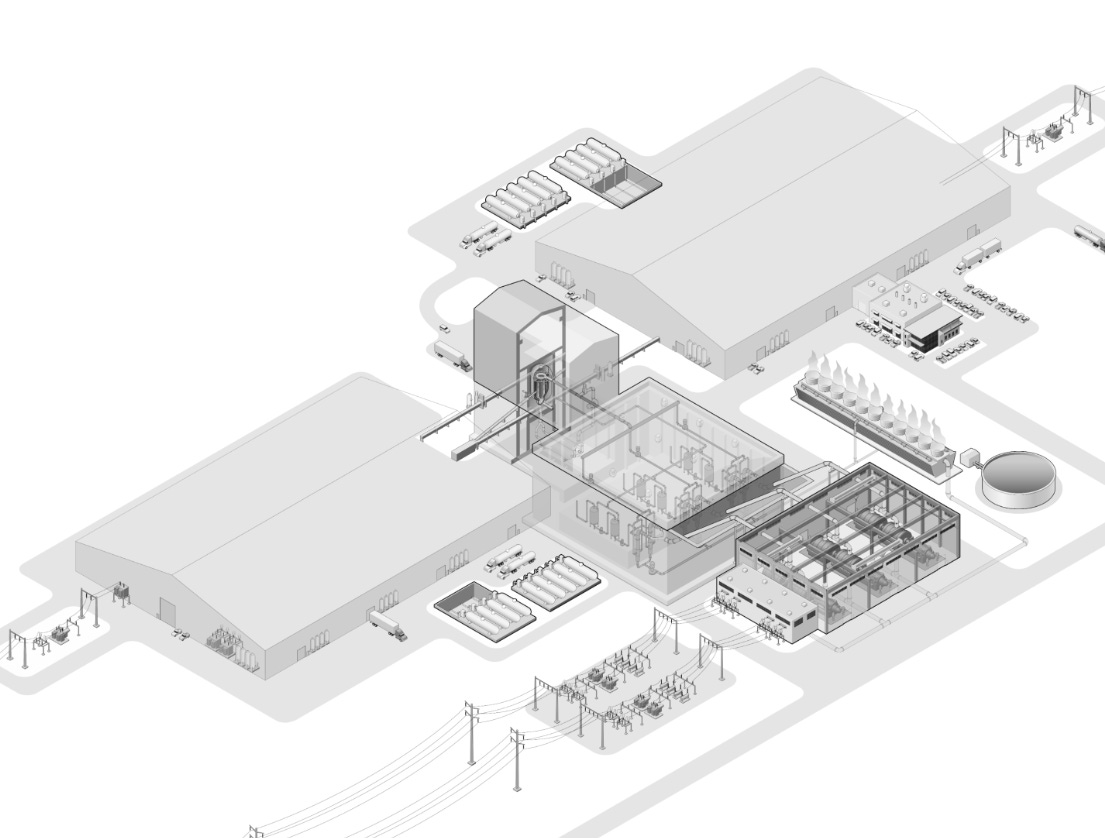

Each shot would release 450MJ of energy (roughly 13l of gasoline). Multiply by 10 shots per second and you get 4500 MWth. Roughly half of this is lost during the conversion to electricity, so this is roughly 2GWe, of which 500MWe have to be used by the lasers, leaving 1.5 GWe for the grid.

Inertia aims at bringing down the cost of the NIF targets by replacing the gold-lined depleted uranium hohlraums with mass-manufactured lead counterparts, which have already been tested at NIF. Stamping out lead targets is apparently close enough to ammunition manufacturing to have some hope of vastly reduced costs. Given that each power plant would consume 864 000 of such targets every day, this seems like a rather critical assumption.

An additional advantage of using hohlraums is that they can protect the frozen D-T fuel pebble from the kinetic and thermal impacts of being injected into the hot reaction chamber at high speed.

Additionally, there are supposedly unresolved physics questions with regard to the direct-drive, like the uncertainties in laser-plasma interactions, which might reduce the theoretical advantage of direct-drive schemes significantly.

While NIF’s goal has been to make pristine targets to maximize fusion output of their undersized lasers (relatively speaking, given that they are of have been by many metrics the world’s most powerful), Inertia’s goal is to use a somewhat overpowered 10 MJ driver to overcome the challenges of less-pristine, mass-produced targets.

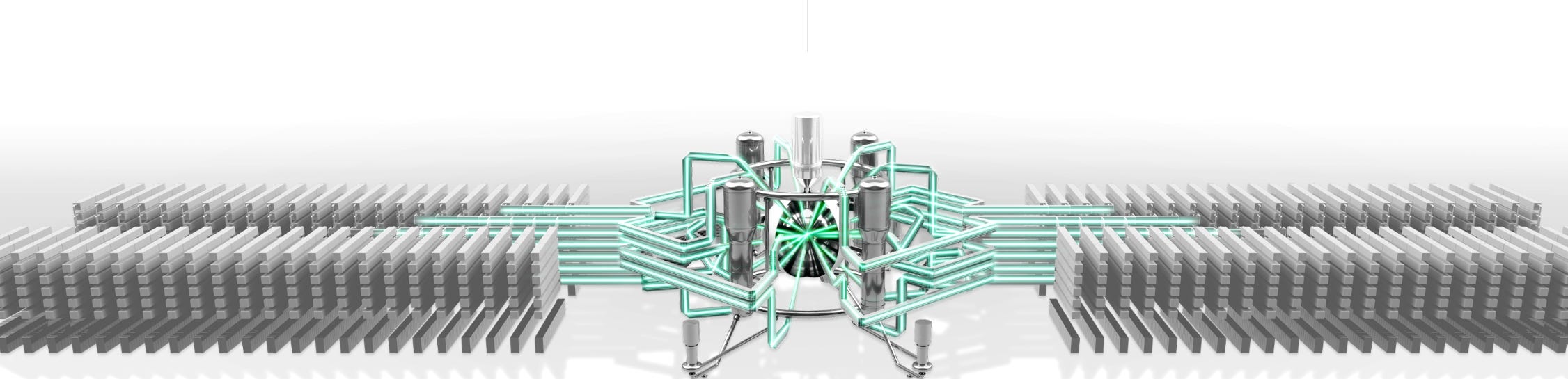

The dreaded first wall problem is dealt with by decoupling the laser driver from the reaction chamber and making the latter disposable. The chamber is a multi-meter diameter shell made of metal with holes in the top and bottom to let laser light through. The walls of the chamber are actually pipes though which a liquid lithium alloy is pumped as coolant. That lithium is also the breeding material for the tritium used in the fusion process itself.

Inertia wants to manufacture the chamber from cheap steel materials and plans on replacing it every 3-5 years.

The 10 MJ laser will be the most energetic ever built. Each beamline will have to handle a factor of 10 or so more energy than any prior design. Yet, the most challenging part will be to acquire enough diodes for pumping the laser material. The world does not produce enough of them. However, another kind of laser-diode, the Vertical-Cavity Surface-Emitting Laser (VCSEL), used in smart phones, has seen production numbers increase by multiple orders of magnitude and their cost fall by multiple orders of magnitude in a span of 5-7 years. This is seen as a mere question of capital invested, not a physics or engineering challenge.

Same, but different

Companies like Focused Energy or GenF are investigating the direct-drive approach, ditching the hohlraum and trying to deposit more energy directly into the fuel. Notably, two of Focused Energy’s scientists - Pravesh Patel and Debbie Callahan - played pivotal roles in NIF’s ignition campaign.

Theoretically, the direct drive should increase the gain for the same laser energy by at least a factor of 5 or more. Focused Energy claims that their proprietary, mass produced Pearl™ fuel capsules will increase output 30x compared to the current NIF indirect-drive fuel system.

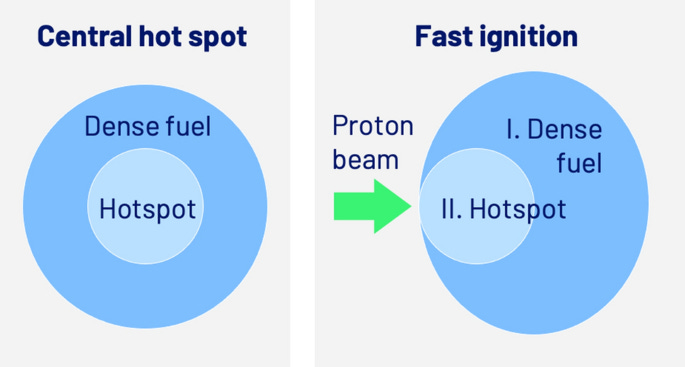

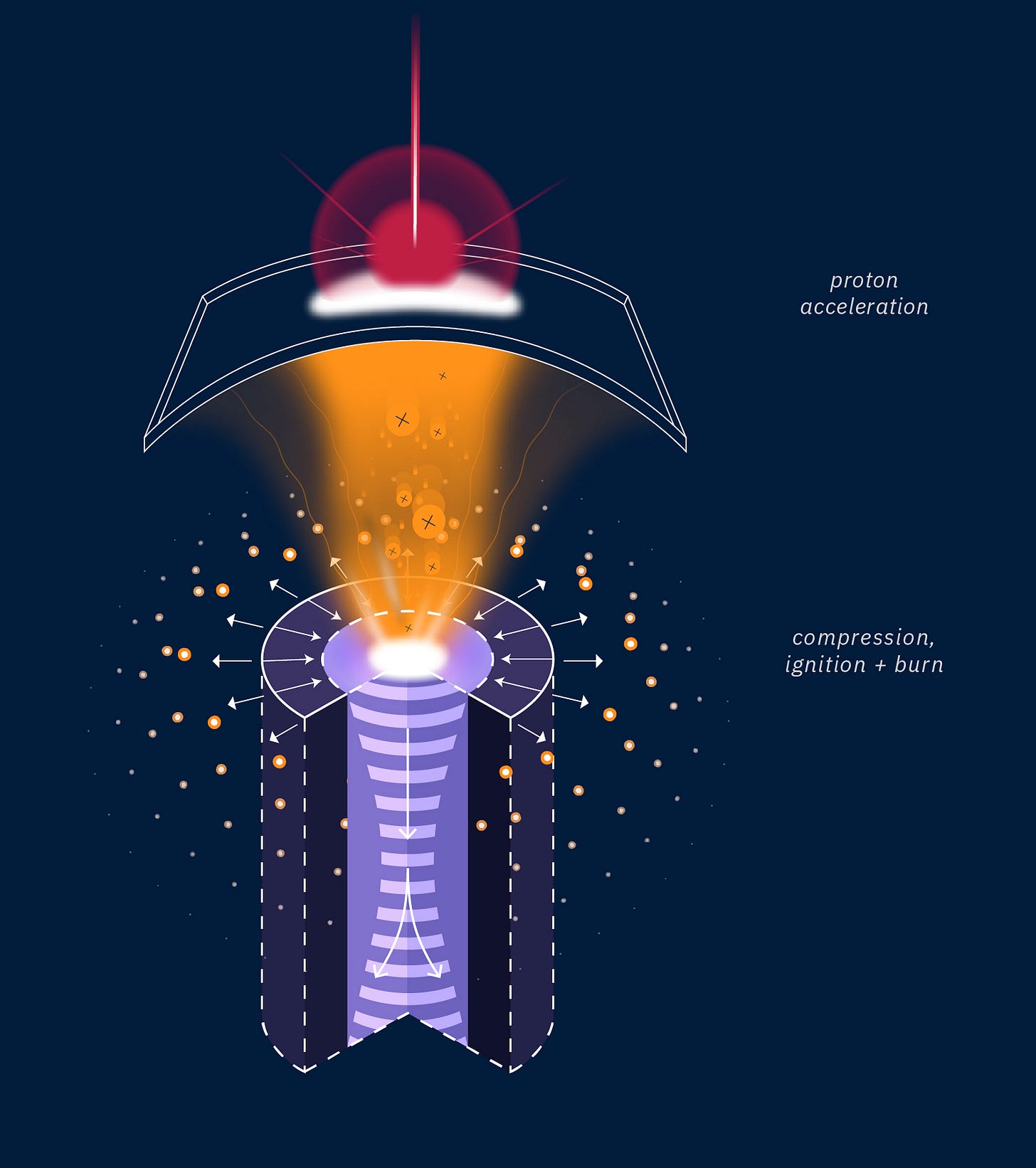

One of the founders of Focused Energy, Markus Roth, is also a pioneer in what is called fast proton ignition. Instead of trying to squeeze the fuel pebble perfectly, a specifically designed metal foil is inserted into the target, which emits neutrons when it is hit by a specific laser. The idea is that you can decouple the compression and the ignition of the fuel. Instead of relying on a perfect compression and ignition from the very center of the fuel, you can create an off-center local hotspot in the pre-compressed plasma, which will start the fusion reactions. Just like a spark plug does in an internal combustion engine. This technique should also help with some amount of asymmetric compression - at the cost of a somewhat more complex target.

While it is unclear to me, whether Focused Energy is still looking at using this approach (former versions of the website and interviews were more explicit about it), it is clear that Focused Fusion and GenF appear to also target the use of diode-pumped solid state lasers and power plants between 1 and 1.5GWe output.

One advantage of using many of these smaller lasers is that individual units (about a 1000 for Inertia and at least several hundreds for Focused Fusion) can be replaced more easily and very probably even while the power plant is running, possibly creating a highly reliable and serviceable fusion system architecture.

The same, but very different

Several companies, like Innoven, Xcimer or LaserFusionX, opt for another type of laser, so called excimer lasers, where a gas mixture (for example KrF or ArF) is used as laser medium instead of a glass.

These are promising, because they are fairly inexpensive to make, simple in construction, and about 10x as efficient as NIF’s flash lamps.

The theory seems to be, that although there were significant advancements in solid-state laser technology since the NIF was built, solid-state glass systems are still very expensive, not shown to be scalable to 10 MJ, and they would still need a great many of beamlines and subsequent holes in the reactor chamber.

Xcimer for example plans to use just two beams and therefore very few holes in the reactor chamber. This makes the use of a liquid first wall possible. They plan to improve on the HYLIFE reaction chamber, where a thick, liquid layer of a molten salt mixture absorbs the fusion neutrons, breeds tritium and is used to as coolant.

The liquid layer should also offer enough robustness to be able to use larger targets, thereby reducing the repetition rate to about 1 Hz.

These benefits come - as everything in engineering - with a cost.

Several orders of magnitude separate the largest excimer laser built to date from the sizes needed for a commercial fusion plant, so they carry scientific risk in their scaling.

The most frequently used gases are toxic, which might carry some risk of public acceptance. While excimer lasers are roughly 10x as efficient as flash lamps, they are still only approximately 7% efficient - approximately half of modern solid-state lasers. On the flip side, the excimer laser produce light in the ultra-violet range, which eliminates the need for additional optical components relative to solid-state lasers. However, the UV light is much shorter wavelength and carries different focusing characteristics than the NIF.

This change in wavelength requires different optical components in the system, for which a supply chain has to be build. A major challenges might be the forming of high fidelity, temporal pulse shapes, which have not been demonstrated in excimer lasers.

The same, but completely different

All of the former companies opt for using D-T fuel. This reaction releases high energy neutrons, which intruduce a lot of engineering challenges, like converting their energy to electricity via a standard thermal cylce, embrittlement of structural components, activation of components, radiation protection for expensive optical and electrical components and measurement equipment and so on. Alternative fusion fuel, like D-D, D-³He or p-¹¹B, while theoretically possible, are far, far harder to ignite

In contrast, the D-T reaction is the most efficient fusion reaction possible. D-T fusion ignition occurs at a “mere” 150 million degrees C, instead of D-D’s 500 millon degress C and is additionally releasing about 3.5x as much heat energy per fusion reaction. The other fuels need even higher temperatures and confinement, but would release a larger percentage of the fusion energy in the form charged particles, which could be converted to electricity efficiently without using a thermal cycle.

While a neutron-free reaction does simplify the plant design and operation, they would not be truly neutron-free in practice: D-³He releases neutrons via unavoidable D-D reactions, and p-¹¹B will do so as long as any trace of deuterium is present in the fuel.

But these challenges do not faze companies like Marvel Fusion, HB11 or Blue Laser Fusion. All of them are targeting inertial confinement fusion with p-¹¹B fuel. HB11 for example wants to use the proton fast ignition explained above to ignite a compressed p-¹¹B fuel pellet. All of them seem to target the usage of many, commercial lasers that are combined for a power plant system.

These approaches cannot rely on the same amount of public, published research and experimental facilities. D-T inertial confinement fusion is currently the only approach to fusion that can rightly claim that it achieved ignition and that there are few - if any - physical barriers left.

The engineering challenges remain quite daunting, though.

Especially with the usage gravitationally confined fusion plasmas coupled with non-dispatchable generators, also known as solar, growing a breakneck speed.

All new forms of power generation will have to compete in a world with decentralizrd, somewhat stochastic generation and storage against the backdrop of managing humanity’s impact on the carbon cycle.

What would you put your money on?

The only proven physical approach with the need for scaling some orders of magnitude in the industrial production of pumping diodes? A somewhat relaxed industrial challenges, but more of a physics risks by using direct-drive (with or without fast-proton ignition)? An entirely different sort of laser with resumably fewer manufacturing challenges, but higher pyhsics risk? Or even for a new fuel, possibly even with direct energy conversion to electricity?

Trillions of dollars are riding on the answer to this question.

Exceptional breakdown of the competitve landscape post-NIF ignition. The observation that Inertia needs to manufacture 864,000 targets per day really crystallizes why target fabrication might actully be the binding constraint rather than laser technology itself. What's fascinating is how each approach essentially trades known engineering risks for unknown physics risks, from excimer scaling challenges to p-11B's substantially higher ignition thresholds. The fact that solid-state laser diode production represents a capital deployment problem rather than a fundamental physics barrier suggests the indirect-drive refinements might have a clearer path to commercialization thanthe more exotic fuel cycles.